By 1894 most sympathizers realized that the defiance of the anarchists exceeded defensible bounds, and the out rages died out quickly. But their effects remained. Anarchism served not only to unsettle the political smugness of the Third Republic, but also to challenge any formulated aesthetic. The dynamism of prewar artistic activity ran a close parallel to anarchism; postwar Dada and surrealism look like its artistic parodies. By acting on their ideas, the anarchist "martyrs" inspired artists to demonstrate as boldly.

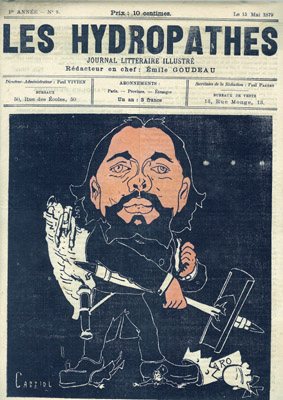

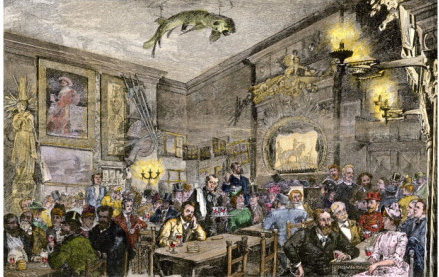

And so they had been doing since the eighties in the new setting of the literary  cabaret. The organized yet authentic Bohemia of the Chat Nair, the most famous of the cabarets, was a salon stood on its head. Its origins go back to a group of young Latin Quarter poets, chansonniers, and painters, calling themselves the Hydropathes, who had begun meeting regularly in the seventies to recite, sing, and issue a magazine. Among them were the sardonic poet Charles Cros, close friend of Rimbaud and Verlaine and legitimate inventor of a pre-Edison phonograph, and Al phonse Allais, chief fumiste (perpetrator of tall tales and hoaxes) and short-story writer, with the mixed talents of Poe and Mark Twain. In 1881 an unsuccessful painter named Rodolphe Salis had the idea of opening a cabaret with its own weekly paper and literary evenings. Serving both as chief performers and dependable clientele, the entire Hydropathe group let itself be lured across the Seine to Salis' Chat Noir on the slopes of Montmartre. Within a few months the establishment was turning away customers attracted by wild stories and farcical publicity. The Chat Nair claimed to have been founded under Julius Caesar and displayed on its cobwebbed walls "cups used by Charlemagne, Villon and Rabelais." The surly waiters wore the formal garb of the Academie frangaise, and Salis insulted each customer as he entered. No one had tried such a "democratic" enterprise before, and the snobs loved it. A few years later Aristide Bruant opened his famous Le Mirliton, where he served as rudest of hosts and peram bulating singer, probably the best of the era. A dozen more such establishments flourished until the turn of the century.

cabaret. The organized yet authentic Bohemia of the Chat Nair, the most famous of the cabarets, was a salon stood on its head. Its origins go back to a group of young Latin Quarter poets, chansonniers, and painters, calling themselves the Hydropathes, who had begun meeting regularly in the seventies to recite, sing, and issue a magazine. Among them were the sardonic poet Charles Cros, close friend of Rimbaud and Verlaine and legitimate inventor of a pre-Edison phonograph, and Al phonse Allais, chief fumiste (perpetrator of tall tales and hoaxes) and short-story writer, with the mixed talents of Poe and Mark Twain. In 1881 an unsuccessful painter named Rodolphe Salis had the idea of opening a cabaret with its own weekly paper and literary evenings. Serving both as chief performers and dependable clientele, the entire Hydropathe group let itself be lured across the Seine to Salis' Chat Noir on the slopes of Montmartre. Within a few months the establishment was turning away customers attracted by wild stories and farcical publicity. The Chat Nair claimed to have been founded under Julius Caesar and displayed on its cobwebbed walls "cups used by Charlemagne, Villon and Rabelais." The surly waiters wore the formal garb of the Academie frangaise, and Salis insulted each customer as he entered. No one had tried such a "democratic" enterprise before, and the snobs loved it. A few years later Aristide Bruant opened his famous Le Mirliton, where he served as rudest of hosts and peram bulating singer, probably the best of the era. A dozen more such establishments flourished until the turn of the century.

By 1885, in an operation twice delayed by the elaborate maneuvers of Hugo's funeral, the rowdy crowd of the Chat Noir burst out of its old quarters and paraded in costume through the streets with a mounted escort to occupy an entire building in the Rue Victor-Masse. The inaugural banquet and festivities included among the guests (for once the account in the Chat Noir paper told the truth) Leo Delibes, Maupassant, Jules Lemaitre, Huysmans, Villiers de l'Isle-Adam, Waldeck-Rousseau and eleven other deputies, two Paris mayors, and three respected septuagenarians: Renan, Bouguereau, the academic painter, and Theodore de Banville, the Parnassian poct, The weekly paper thrived, publishing poems by Verlaine and Mallanne, humorous chroniques by everyone, and cartoons by Forain, Steinlen, Caran d'Ache, and Villette. The chansonnier ramatist Maurice Donnay had the dizziest success of all: ten plays and tvventy years after his debut at the Chat Noir, he was elected to the Academie française - the real one - and was not out of place. The most original undertaking on the three-story premises was the Theatre d'Ombres, which developed the crude technique of shadow plays into a convincing art form ten years before the advent of films. This menagerie of writers turned performers of their own work kept Paris entranced for a decade; their brand of sentimental humor both mocked and exploited the era.

By 1885, in an operation twice delayed by the elaborate maneuvers of Hugo's funeral, the rowdy crowd of the Chat Noir burst out of its old quarters and paraded in costume through the streets with a mounted escort to occupy an entire building in the Rue Victor-Masse. The inaugural banquet and festivities included among the guests (for once the account in the Chat Noir paper told the truth) Leo Delibes, Maupassant, Jules Lemaitre, Huysmans, Villiers de l'Isle-Adam, Waldeck-Rousseau and eleven other deputies, two Paris mayors, and three respected septuagenarians: Renan, Bouguereau, the academic painter, and Theodore de Banville, the Parnassian poct, The weekly paper thrived, publishing poems by Verlaine and Mallanne, humorous chroniques by everyone, and cartoons by Forain, Steinlen, Caran d'Ache, and Villette. The chansonnier ramatist Maurice Donnay had the dizziest success of all: ten plays and tvventy years after his debut at the Chat Noir, he was elected to the Academie française - the real one - and was not out of place. The most original undertaking on the three-story premises was the Theatre d'Ombres, which developed the crude technique of shadow plays into a convincing art form ten years before the advent of films. This menagerie of writers turned performers of their own work kept Paris entranced for a decade; their brand of sentimental humor both mocked and exploited the era.

The atmosphere of permanent explosion in artistic activity is evidence not only of anarchistic tendencies but also of the fierceness of its experiments. New reviews appeared, principally La Vogue (founded in 1886; in a brief life of nine months it reached the staggering circulation of 15,000 and published major texts by Mailarme, Verlaine, Rimbaud, Villiers de !'Isle-Adam, and Lafargue), the long-lived Mercure de France ( 1890), with its monthly banquets and weekly editorial receptions, and the Natanson brothers' Revue Blanche ( 1891) . The Salon des Independants outgrew one building after another with more and more work from young painters, while ethnological museums were being filled with astounding art from Africa, the Pacific, and Egypt. . . .

By 1885 there was a crying need for fresh outlets of expression, a need met in part by the new literary re views, the Salon des Independants, and influential private gatherings of artists such as Mallarme's mardis ( 1884) and Edmond de Goncourt's grenier ( 1885). Even more important, cafe and cabaret provided the artist with social independence and produced their own variety of conversational wit and brilliance. The cultured public, no longer dominated by the salon, gradually came to realize that there existed a small group of people thinking and living and creating beyond the pale of ordinary behavior. Today the persevering remnants of the avant-garde are generally scoffed at, often exploited, and occasionally glorified be yond all measure. Modernism wrote into its scripture a major text, which demands, at least in retrospect, our gratitude: the avant-garde we have with us always.

Like everyone else, they had their own banquets. These untrammeled  gatherings tended to gain momentum toward wild farce or orgy. The Lapin Agile (also known as the Lapin a Gill or La peint A. Gill) [A play on words in French -- The Agile Rabbit and The Rabbit of Gil sound alike], the Montmartre cabaret that succeeded the Chat Noir around the turn of the century, housed many celebrations, which always included Frede, the bushy-bearded proprietor, and his unhousebroken donkey, Lolo. A group of young artists, inspired by the author Dorgeles, there concocted the celebrated hoax of a canvas brushed entirely by Lolo's twitching tail. The resulting work, distinctly "impressionist" in style, was hung at the Salon des Independants with the title "And the Sun Went Down over the Adriatic." Dorgeles signed it "Joachim Raphael Boronali," and the painting was praised by a re spectable number of critics on their marathon tour of the show.

gatherings tended to gain momentum toward wild farce or orgy. The Lapin Agile (also known as the Lapin a Gill or La peint A. Gill) [A play on words in French -- The Agile Rabbit and The Rabbit of Gil sound alike], the Montmartre cabaret that succeeded the Chat Noir around the turn of the century, housed many celebrations, which always included Frede, the bushy-bearded proprietor, and his unhousebroken donkey, Lolo. A group of young artists, inspired by the author Dorgeles, there concocted the celebrated hoax of a canvas brushed entirely by Lolo's twitching tail. The resulting work, distinctly "impressionist" in style, was hung at the Salon des Independants with the title "And the Sun Went Down over the Adriatic." Dorgeles signed it "Joachim Raphael Boronali," and the painting was praised by a re spectable number of critics on their marathon tour of the show.